Behind the Buzzword: What ‘AI’ Really Means at Chippy

404: Intelligence Not Found

Our History with LLM’s

We’re not strangers to large language models here at Chippy.

In fact, our journey with them started long before “AI” became the tech industry’s favourite buzzword. Back at university, I spent my time experimenting with early-generation LLMs and even picked up a British Computing Society award for that work.

Since then, things have changed dramatically. Hardware is faster, datasets are enormous, and billions of pounds have been poured into the generative AI gold rush. What once ran on a university cluster now hums across racks of GPUs in the cloud.

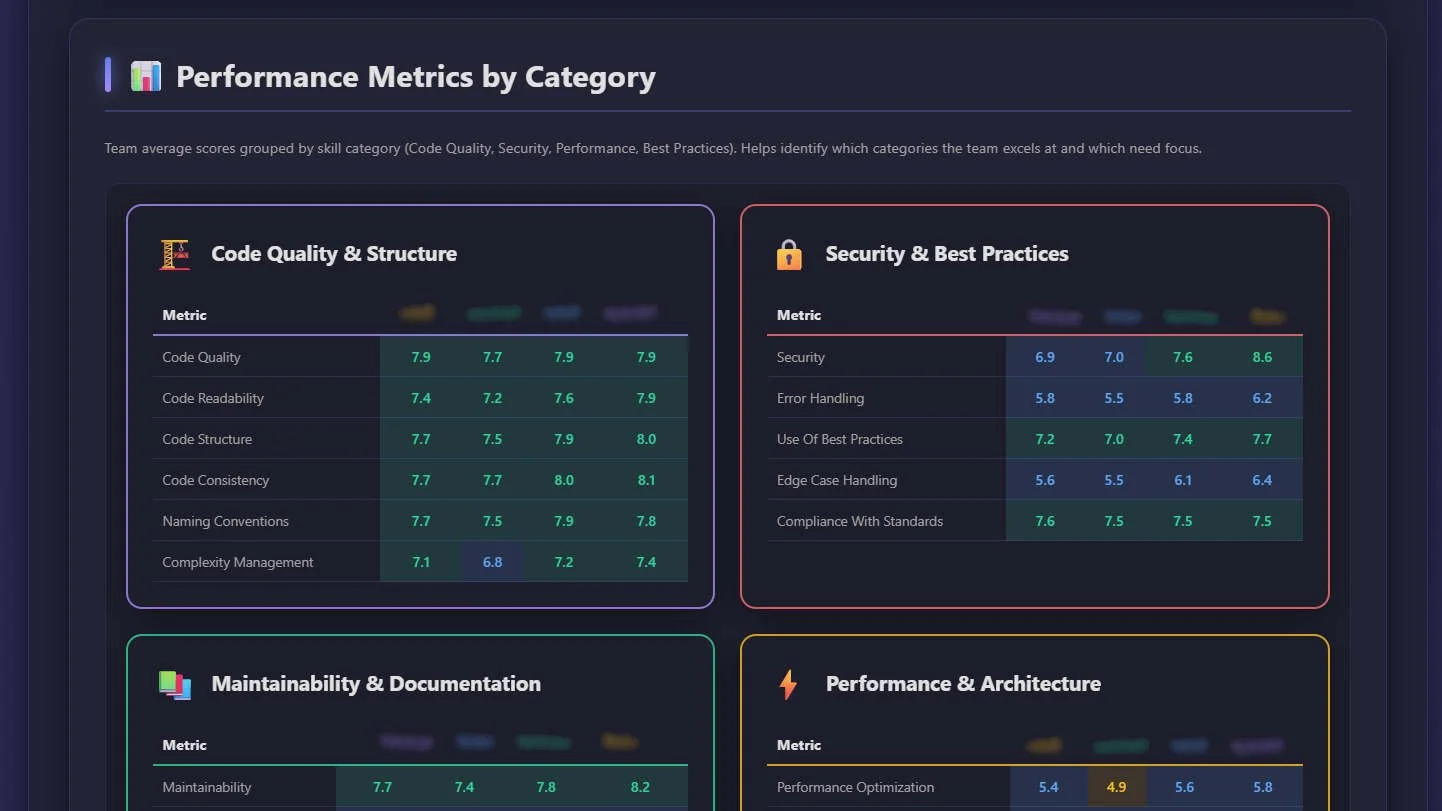

Code Parrot by Chippy Digital

At Chippy Digital, we’ve been putting that evolution to work; and not in a hype-driven way, but in ways that genuinely help our developers. For the past few years, we’ve run internal systems that quietly assist our engineers: analysing commits, suggesting improvements, and silently scoring patterns to surface insights. Those experiments evolved into a developer dashboard that’s now used across the organisation, helping us understand code quality, collaboration, and efficiency like never before.

But as we’ve gone deeper, one thing has become increasingly clear: the more you work with so-called “AI,” the less it feels like intelligence, and the more it looks like really fast pattern matching.

The tools we've tried, what actually stuck, and why it matters

ChatGPT Codex or Anthropic Claude Code

Our toolkit has evolved, but what's actually changed is worth examining carefully. We've experimented with OpenAI's Codex, worked with Claude via APIs, run local models through Ollama, and recently started using Claude Code from the terminal. On the surface, each step looks like progress; for better integration, for faster feedback loops, and for more control over where computation happens.

However, what's really happening underneath? Because we're not getting smarter models, that’s for sure. We're getting the same pattern-matching machinery in different arrangements. OpenAI's API gives us remote access to their pattern-matcher. Ollama packages a pattern-matcher to run on our own hardware. Claude Code wraps a pattern-matcher in terminal tools so it can edit files and run git commands. Each tool solves a real problem; latency, privacy, workflow integration, but none of them are becoming or showing more intelligence?

Ollama runs on consumer hardware with GDPR compliance and no per-request costs, which matters for practical reasons. Claude Code lives in your terminal and handles multi-file edits and git workflows which makes development faster; but these are infrastructure improvements, not intelligence improvements. The model still can't reason. It still can't understand causation. It still hallucinates confidently when it doesn't know something. It just does all of that in a more convenient and powerful wrapper.

What Anthropic and OpenAI have actually given us is better access to their computational resources, to data sources, to integration points where we can feed these LLM’s useful information. We can now run them locally without API calls. We can now point them at our codebase before asking for changes. We can now chain them into workflows that feel like collaboration. None of that makes them intelligent. It just makes them more useful.

And that distinction matters, because the moment you assume the tool is thinking, you start relying on it the wrong way.

The Real Trade-Off: Power Without Wisdom

Better integration creates problems. When tools get tighter with your workflows and the AI tool lives in your terminal, can edit files directly, run git commands, manage pull requests, it also reduces the friction that used to keep those tools honest. A web interface requires a click, a moment to think. A terminal command is immediate. That immediacy is powerful and dangerous in equal measure.

The Inter-Parliamentary Union states that the nature of human oversight depends on the type of AI application. It can happen during development, on an ongoing basis, or once the system is in production.

However, I think they need to be much clearer and stronger in their messaging, and move away from calling it AI. As soon as people start to think what they are interacting with is intelligent they begin to trust it more, and this trust is misplaced. Oversight is only one part, complete review and thorough testing is far more crucial.

CSV to JSON using ChatGPT

The honest conversation about these tools is this: they won't work without you. The moment you assume they're correct and stop looking, they will confidently go down entirely wrong paths. In practice, what works is parallel work. You're building something in one window, in the traditional sense; thinking, typing, deliberating. Claude Code or a local LLM is working in another window, handling the tedious bits: converting data formats, writing comments, restructuring CSV into JSON, scraping and reformatting.

You glance over periodically. You catch the mistakes early. The more an expert user provides feedback, noticing inaccuracies and understanding context, the more practical and attuned the system becomes to nuances according to LexisNexis, but in reality this is false. These models are not learning from your interactions, they are purely inference models, meaning they will act on what you have said, fix their mistakes and then make that same mistake again on the next prompt.

Ultimately, this isn't replacement, developers aren’t going to lose their jobs. It's augmentation, but only if you treat it as augmentation. The developers who get value from these tools are the ones who glance at the output, who maintain a backup of what they're doing, who keep their git history clean so they can revert if something goes sideways. They're not delegating their judgment. They're delegating their busywork, and keeping their judgment handy.

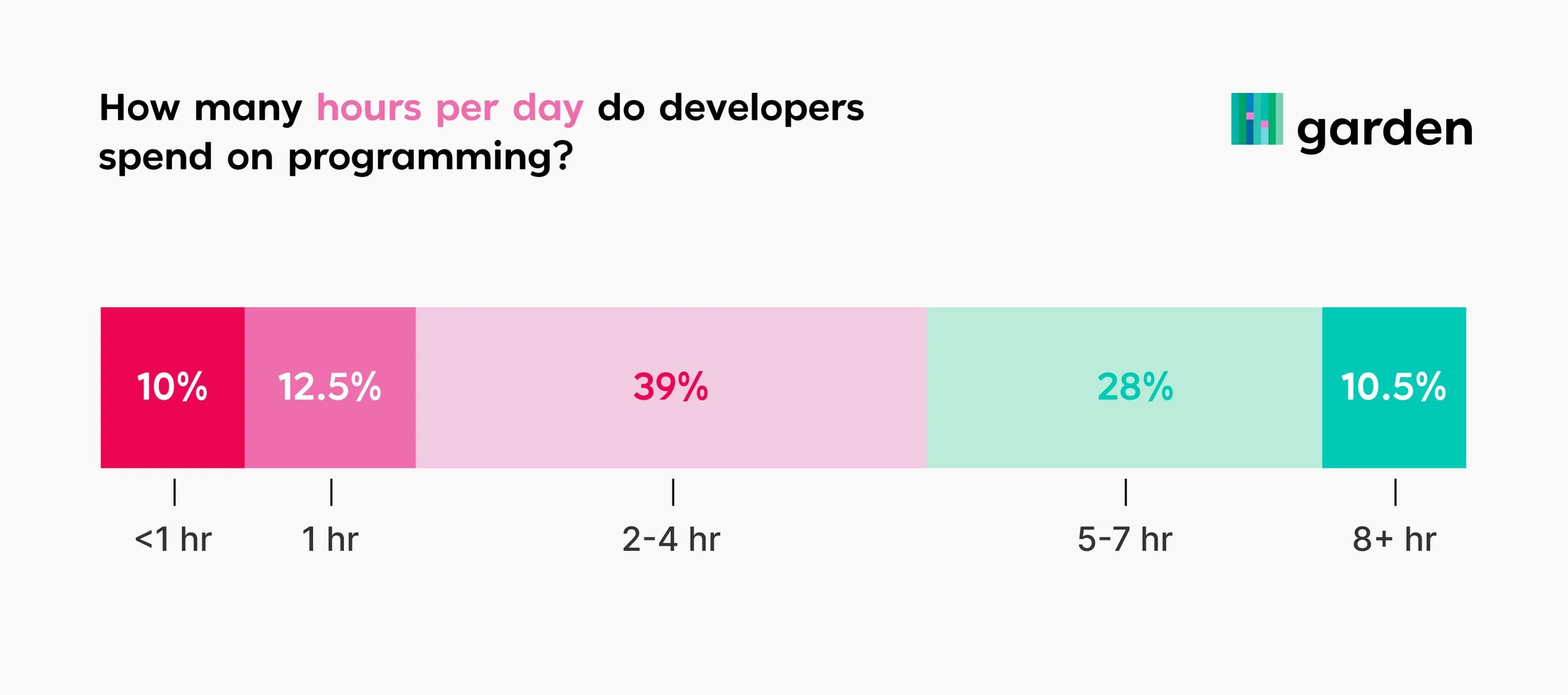

How many hours per day do developers spend on programming?

And here's the thing nobody talks about much: developers already know this. We spend half our time on work that feels invisible; documentation, reformatting, data transformations, comments that explain the obvious. For legal professionals, accountants, researchers, customer service teams the same applies: they're often handling menial tasks that don't feel like "real work" but consume enormous amounts of time.

An AI tool that handles that faster, even imperfectly, saves real time. Even if a human has to review and clean it up afterward, the net time saved is often significant.

The shift from "how do we replace developers" to "how do we multiply what they can accomplish" is where the real value lives. Not in the tool being smarter. In the developer being faster at the work that actually matters.

Teaching the Machine: An Agile Framework for Pattern-Matching

The real work isn’t just using these tools, it’s setting them up so they don’t fail, and that isn’t a one-off task, it’s a discipline.

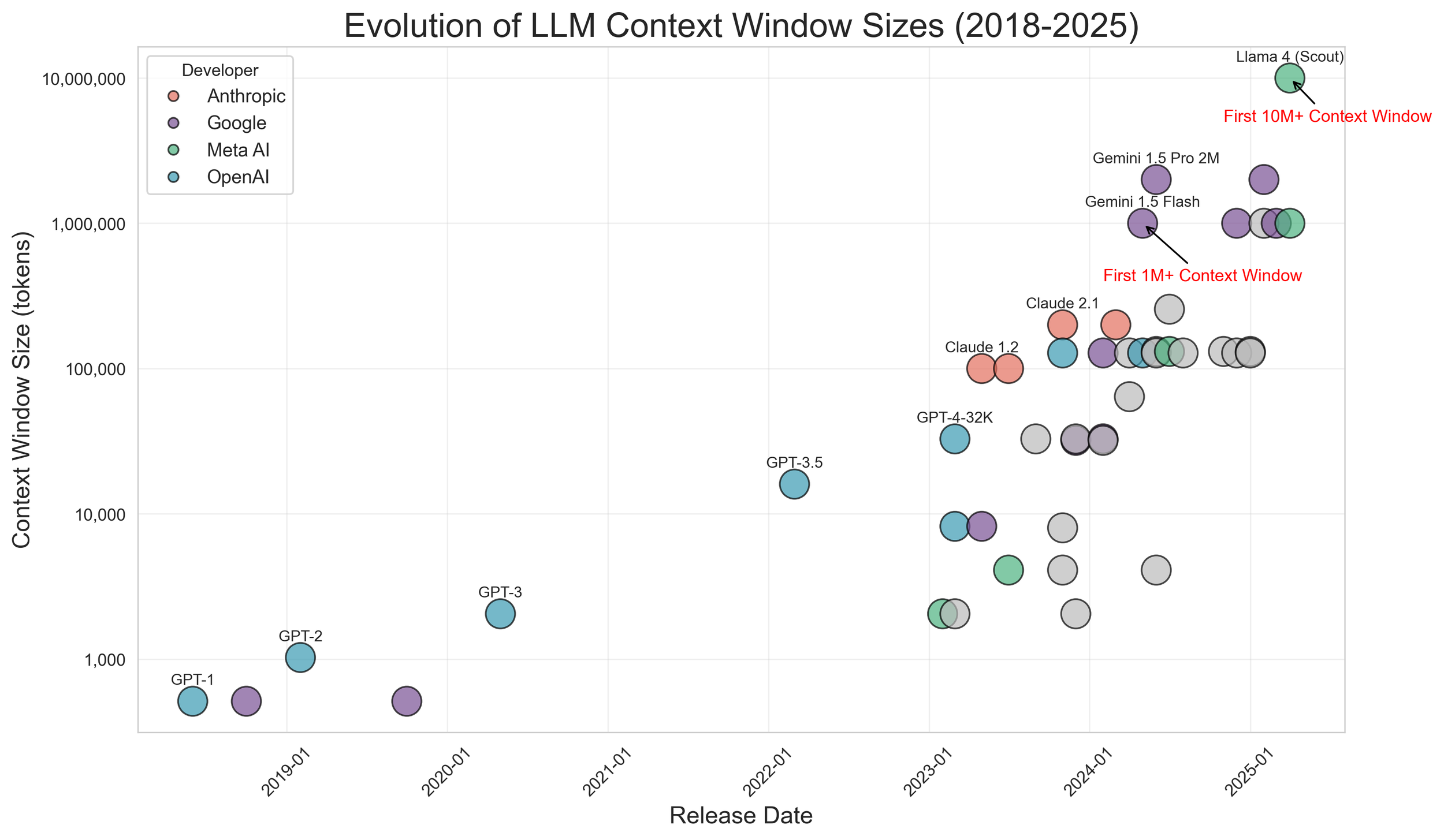

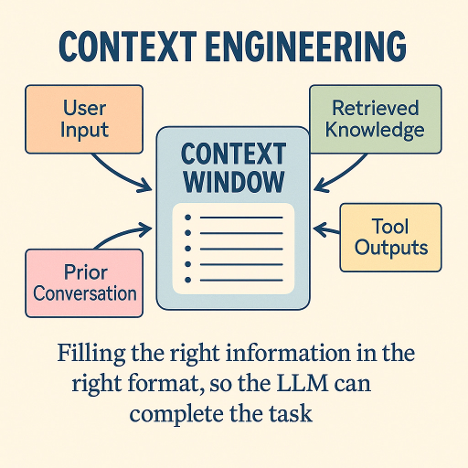

LLMs do not learn from prompts in the traditional sense. They have a finite context window, the set of tokens, including both your prompts and the model’s own responses, that they can consider at once. Anything outside that window is effectively invisible. Good context management is about ruthlessly deciding what goes in, in what order, and how it is structured, so the model has the right information at the right time.

Evolution of LLM Context Window Sizes (2018-2025)

Start by having the model document what already exists: your codebase structure, your data schemas, your team’s conventions, and why they likely follow them. This is not for humans, it is for the LLM to reference immediately. The goal is to provide high-signal information that fits within its context limits. System prompts should be precise and direct, not overly prescriptive, not dangerously vague, so the model can act on concrete signals without misinterpreting them.

Next, ask the model to challenge its own understanding, what might be ambiguous, and what assumptions it is making. Then have it break tasks into smaller chunks that it can reason about independently. This is crucial, because early mistakes can persist in the context window, influencing later responses. Decomposing problems and pruning context helps prevent these errors from compounding.

What is context engineering?

This is where traditional prompting stops and context engineering begins. You are effectively building a scaffolding for the LLM, organising information to maximise relevance within its limited memory, structuring outputs, defining scope, and setting evaluation criteria. Each iteration refines that scaffolding, you run it on new data, review failures, update documentation, and adjust prompts to keep the context coherent and relevant.

It is not intelligence, the model is not learning. What is improving is your management of its context window, your ability to feed it exactly the right tokens, in the right order, so it behaves predictably and reliably. With careful upfront work, a well-prepared context allows the model to operate consistently, reduce mistakes, and become a genuinely useful tool.

Over time, you can guide the LLM to do much of this itself through strategic questions. You can ask it to create a document for a particular purpose, analyse a set of outputs, identify gaps in its own work, run tests or analyses against what it has done, and review that feedback. Then, you can have it update its earlier documentation based on what it has discovered. You are not giving exhaustive prompts, you are guiding it to be agile and work smart. In doing so, the AI is invisibly building a context for any future task, retaining what it needs to know to operate effectively. This is why LLMs appear intelligent, but in reality, they are not.

Conclusion: Intelligence Isn’t in the Machine, it’s in the User

LLMs are not a replacement for expertise. They are powerful extensions of it. Their apparent intelligence comes not from thinking, but from how well you manage context, structure prompts, and integrate them into your workflows.

The real value lies in augmenting human effort, freeing people from repetitive, menial tasks so they can focus on judgment, creativity, and problem-solving. When treated as augmentation rather than intelligence, these tools multiply what teams can accomplish safely, efficiently, and reliably.

The machine does not get smarter, but the user does, and that is where true innovation happens.